Review of Film

This post assesses the key learning points and reflections I have from watching the film L’amour de court (Cartier-Bresson, 2001.)

The video opens with one of his most famous images shown below in Figure 1.

It is astonishing that Cartier-Bresson claims that this image was pure luck and that he had simply stuck his camera through a fence. What follows in his video is more impactful to me than this specific example though.

I should think that any photographer will have wished for a specific scene at some time or other but are we really sure that we have not been there and simply failed to notice the scene?

Cartier-Bresson states “What matters is to look. But people don’t look. They press the button.”

This perspective seems to reverse the direction of the decisive moment. Whilst one might be tempted to think that we are ready to capture such a moment and we simply need it to happen, Cartier-Bresson seems to be saying that these events are happening all around us and it is our observational skills that need to be fostered to find them. The decisive moment is the moment the photographer observes the scene, not the moment the event happens.

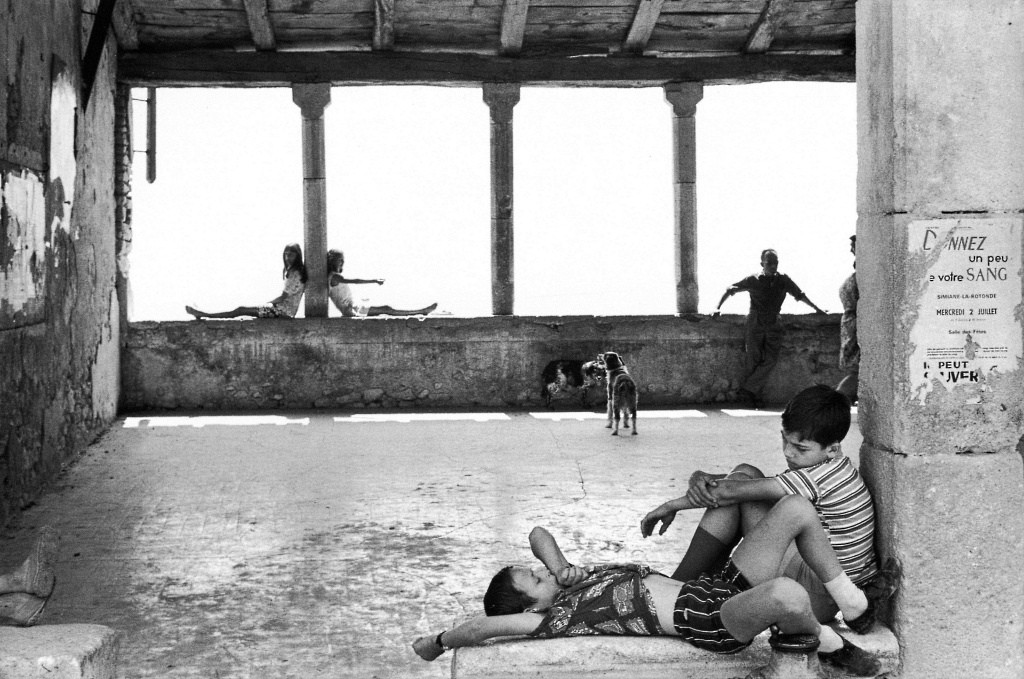

Adopting this essential perspective seems to be a way of life for Cartier-Bresson. From the same video Yves Bonnefoy states “While others are distracted and unobservant, Henri is on the lookout, ready to react, not even needing to stop”. Bonnefoy describes walking through his local village and passing by the town square, usually deserted, and Cartier-Bresson capturing the image shown in Figure 2, barely breaking stride or conversation to do so. The resultant photograph is perfectly balanced to the point that it looks almost as if it could have been staged.

It seems Cartier-Bresson developed a practice of always looking, whatever else he may have been doing.

In Cartier-Bresson’s own words from the film “you have to be receptive, that’s all. Just be receptive and it happens.”

Lastly, Cartier-Bresson’s photographs tend to be taken without the subject being aware. In the film Giacometti states that he prefers it that way else they will “pose, put on a mask and lose sponteniety”.

Perhaps the ultimate demonstration of this was his ability to photograph scenes of clearly upset people at a funeral. Cartier-Bresson is clearly in an amongst the people and the event is a sensitive one and yet there do not seem to be objections. Giacometti commenting “Thus, Henri paints black the shiny parts of his Leica”.

It is not simply the camera that achieves this presence though, it is Cartier-Bresson’s ability to empathise with the people, He does not need to be upset like them, but he can empathise.

Learning Points

I think there are three key learning points from this film:

- The perfect scene is always there, you simply have to be receptive to what is going on in order to observe it. The decisive moment in this context is more akin to the moment the photographer observes the scene rather than the moment the scene happens.

- Being receptive needs to be a permanent practice, be open to the fact that a scene could present itself at any moment.

- Empathy with the subject, can help one as a photographer be present in a scene that might otherwise be inappropriate.

Bibliography

Cartier-Bresson, H. (2001). L’amour tout court. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL707C8F898605E0BF [Accessed 16 Apr. 2017].

Figures

Figure 1. Cartier-Bresson, H. (1932). Place de l’Europe. [image] Available at: http://pro.magnumphotos.com/Asset/-2S5RYDI9CNRQ.html [Accessed 16 Apr. 2017].

Figure 2. Cartier-Bresson, H. (1969). Simiane-la-Rotonde. [image] Available at: http://theredlist.com/wiki-2-16-601-803-view-humanism-profile-cartier-bresson-henri.html [Accessed 16 Apr. 2017].